A petition calling on several major Singaporean banks to end their funding of thermal power plants in developing nations like Vietnam and Indonesia has shed light on the complex, transnational nature of financing for such projects.

The open letter, released last month and signed by 14 environmental groups from around the world—including Greenpeace and Friends of the Earth—singles out DBS, OCBC and UOB for “falling critically behind, not only failing to deliver policy and practical responses to climate change, but instead becoming an increasing part of the problem through the continued multi-billion dollar financing of coal-fired power stations and related infrastructure.”

A close look at one such power plant in Vietnam, the Nghi Son 2, reveals that Singaporean banks are not alone in this activity. According to Market Forces, an affiliate of Friends of the Earth Australia which analyses the financing of development projects, funding will not only come from the above-mentioned Singaporean banks, but also the UK’s Standard Chartered, the Korea Export-Import Bank, the Japan Bank for International Cooperation and several Japanese commercial banks: Mizuho Financial Group, the Bank of Tokyo-Mitsubishi UFJ (MUFG) and the Sumitomo Mitsui Banking Corporation (SMBC). Financing for this USD2.5 billion coal-fired plant, to be located in Thanh Hoa Province just north of central Vietnam, is expected to be finalised by the end of this month.

Unwinding the finances behind a blockbuster project like Nghi Son 2 isn’t easy, but Julien Vincent, executive director of Market Forces, explains how such funding is generally structured.

“Like most other deals in the region it is led by government-backed institutions like the Korea Export-Import Bank, and in the case of Nghi Son 2 it’s largely Korean and Japanese,” he shares. “The way it generally works is they come in and provide a large bunch of loaning interest and long-term credit, and they can do that because there’s some sort of national interest imperative.”

The involvement of these state-linked organisations signals that a project is safe enough for commercial banks to enter the equation and provide further financing. Since funding for Nghi Son 2 has not yet been confirmed, it is unclear exactly how much each bank is set to contribute. But the fact that they’re involved at all is worrying, as the power plant would breach some of their own regulations.

The environmental cost

Several independent analyses of Nghi Son 2’s Environment Impact Assessment (EIA) have concluded that the project would be disastrous for the local environment. Market Forces estimates that the plant would create twice as much CO2 for every unit of generated power in comparison to the average thermal facility in Vietnam.

A report titled “Comments on the Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) of Nghi Son 2 Thermal Power Plant” by the Hanoi-based Green Innovation and Development Centre (GreenID) points out numerous red flags. For example, the plant is just one part of the planned Nghi Son Power Centre, which would include two other coal-fired plants. The EIA, which runs 375 pages and is only in Vietnamese, fails to take one of these other facilities into account, and therefore doesn’t present the cumulative impact.

These power plants will also be located within the huge Nghi Son Economic Zone, home to other industrial sites such as steel and petrochemical refining plants, ship yards and consumer goods export facilities. The EIA excludes these factors when accounting for overall emissions.

Flags fly from fishing boats in Thanh Hoa Province in Vietnam. Peter Stuckings / Shutterstock.com

Nghi Son 2’s impact of local fisheries is also a matter of concern given its coastal location, and GreenID found problems here as well. While the plant’s EIA claims that there’ll be no impact on aquatic species, GreenID points out that the report “does not have [a] record of fisheries species prior to the construction of the plant, so it does not assess the level of reaction of each species to the change of environment, so there is no bases of evaluation.”

The NGO’s studies of ecosystems around four other thermal power plants with similar capacities elsewhere in Vietnam found that fisheries have been decimated. According to their report, fishermen have had to quit fishing in certain areas, while fish farms have had to be relocated away from contaminated water.

Finally, GreenID found that the people living around the Nghi Son 2 site have not been consulted. Therefore, “local people hardly know impacts of the projects in advance. It is only after the plant is constructed and operated that they get to know. That’s why there are many complaints filed by local people afterwards.”

Standards on climate change and energy

DBS and Standard Chartered have borne the brunt of the criticism over Nghi Son 2 financing and how it relates to their corporate environmental policies.

DBS released a new policy on sustainability commitments in January this year. One section states: “DBS will stop financing new greenfield coal-fired power generation projects in OECD/developed markets. In developing countries, DBS will change its focus to more efficient technologies.”

“It’s unfair for people in Vietnam because that means we don’t deserve clean air like people in developed countries”

The fact that their explicit commitment to end funding for coal-fired power plants applies only to developed countries hasn’t been received well in places like Vietnam. “We see that as a double standard,” says Tuong Nguyen, program manager at CHANGE Vietnam, one of the signatories of the petition. “It’s unfair for people in Vietnam because that means we don’t deserve clean air like people in developed countries.”

Tuong and her organisation have taken direct aim at DBS in a separate online petition addressed to Peter Seah, DBS’ chairman, and Piyush Gupta, the bank’s CEO. The letter refers to Nghi Son 2, as well as three other coal-fired power plants that DBS is considering funding in Vietnam.

DBS did not respond to request for comment for this article.

Meanwhile, The Straits Times recently reported that Standard Chartered is reconsidering its potential support for Nghi Son 2 since technical analysis of the project’s Environmental Impact Assessment has revealed that the completed plant would breach the bank’s own publicly-stated position on climate change and energy.

Standard Chartered’s statement on the issue says that the bank “[w]ill not provide debt or equity to new coal-fired power plants which do not achieve a long-run emissions intensity of below 830g/CO2/kWh.” The measurement refers to the amount (in grams) of carbon dioxide per kilowatt-hour of energy production. Lauri Myllyvirta, Greenpeace’s Beijing-based coal and air pollution expert, estimates that Nghi Son 2 would have an average emissions intensity of 890-900g/CO2/kWh, well above the bank’s limit.

In response to questions based on this analysis, a Standard Chartered spokesperson said: “For a potential coal project, we will work with an independent consultant to review the project’s potential impact on the environment and have the consultant report objectively on its projected long-term emissions. Upon getting the consultant’s report, if the findings fall short of our standards, our approach is to first work with the client to try to ensure the project can be aligned with our standards, and if this is not possible, we can and would decline participation. In the case of Nghi Son 2, it is still under review.”

But DBS and Standard Chartered aren’t the only banks running the risk of breaching their own commitments. Like Standard Chartered, Mizuho, MUFG and SMBC are also members of the Equator Principles. Members of this group, which includes 92 global financial institutions, commit to more rigorous standards for project financing and environmental policies.

“[T]he fact that these banks are jumping on board is in violation of something that they’ve signed up to”

Bernadette Maheandiran, research and legal analyst at Market Forces, believes their potential participation in Nghi Son 2 goes against the Equator Principles, as members of the group are required to look into other power sources such as natural gas or renewable energy before throwing their support behind coal. “They need to say that these alternatives are not plausible, and they didn’t do that in this case,” Maheandiran explains. “So the fact that these banks are jumping on board is in violation of something that they’ve signed up to.”

Requests for comment were sent to all the banks concerned in this story, but OCBC was the only other financial institution to respond.

According to Koh Ching Ching, head of group corporate communications, “OCBC has a responsible financing framework and policies that assess environment, social and governance (ESG) risks of the projects and their impact on the environment. In the financing of energy projects, beyond the evaluation of the credit worthiness, we review their Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) reports and perform enhanced due diligence on the operational aspects of the customers’ business activities. Our responsible financing policies are strengthened over time. Environment sustainability is a journey. We seek to positively influence our customers’ behaviours by engaging them in adopting appropriate sustainable practices.”

What Nghi Son 2 tells us about Vietnam’s energy policy

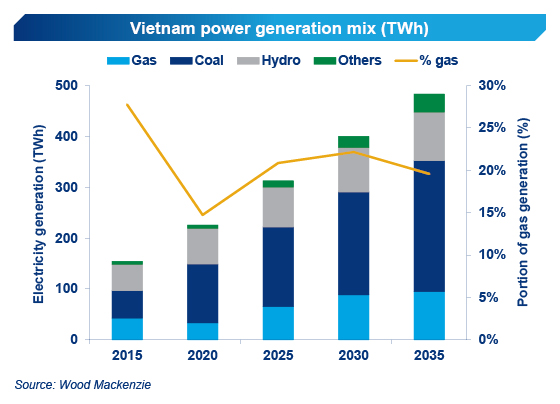

This controversial power plant is emblematic of Vietnam’s energy production strategy over the next decade, a period during which electricity consumption is expected to triple. While many countries around the world are focused on phasing out coal-fired plants, Vietnam is going in the opposite direction.

According to the government’s long-term master plan on power and energy generation, which was approved in March of 2016, the country’s share of power created by thermal plants will increase in coming years.

The plan forecasts that coal-fired thermal power will account for 49.3% of all electricity produced in Vietnam by 2020 before rising to 55% by 2025 and dipping to 53.2% by 2030. By that point, the power sector will be consuming almost 130 million tons of coal per year.

While many countries around the world are focused on phasing out coal-fired plants, Vietnam is going in the opposite direction

Vietnam’s leadership had once planned to enter the nuclear energy sector, with Russian and Japanese firms agreeing to help build plants on the south-central coast. However, this policy was abandoned in late 2016 due to the cost of the proposed facilities. Hydroelectric, wind and solar production is expected to rise by 2030 as well, but coal will still provide the majority of Vietnam’s energy for the foreseeable future.

Tuong of CHANGE Vietnam believes the battle over Nghi Son 2 is just one step in a broader fight against this policy direction. “Vietnam has great potential for developing renewable energy, and we’re not saying we should stop all coal power plants that are in operation,” she explains. “But we want to stress that we need to stop investing into new coal power plants.”

She’s been disappointed by the tepid response from locals and media outlets alike. “We’ve done media training and briefings to provide information on this issue to Vietnamese journalists… but the topic of coal power plants is very sensitive, so it’s hard to do that,” she says. “Even organising a petition in Vietnam is something that we are not officially allowed to do, to ask the government to stop doing something.”

The petition directed towards DBS, which was launched on 6 March, had garnered 713 signatures as of the time of writing. CHANGE is aiming for 2,000 signatures by 22 March.

“We need local voices in this case,” Tuong says. “Otherwise the banks will think the local people didn’t react to this information, so they won’t do anything.”

Source: https://newnaratif.com/

.png)